In late November the Globe and Mail reported, rather breathlessly, that the Toronto Blue Jays were deep into planning the end of their current home the Rogers Centre, once (and always to some) known as SkyDome. Parallel stories urgently proclaimed “Rogers Centre faces wrecking ball.” The reporting indicated that the Jays’ owners Rogers Communications were plotting to demolish the 31 year-old retractable roof stadium and replace it with a more intimate baseball home on the southern part of the present site, accompanied by new development on the newly available real estate at the northern end. The Globe story also mentioned that the Jays are exploring alternate sites if plans for re-developing the existing site don’t take hold, which is certainly a possibility given that while Rogers owns the building, the federal government owns the land.

The Blue Jays promptly issued a statement saying that any potential changes to where they play baseball are still years away. But this story was born out of a persistent challenge the team has faced in trying to find a way to play baseball in a modern baseball stadium. There was a similar, though less definitive story not too long ago that the Jays were doing preliminary exploration of building a new stadium.

The narrative of a new stadium represents a notable shift. Blue Jays President Mark Shapiro has made an extensive renovation of the Rogers Centre one of the centrepieces of his tenure with the team, but after years of teasing the new-look stadium no bullet points of planned alterations or artist’s renderings of the revamped dome have been forthcoming. This long-simmering renovation followed ongoing talk of converting the Rogers Centre to a natural grass surface under the regime of former team president Paul Beeston. The natural grass plan was quietly shelved when Shapiro took over.

The moving targets all speak to an organization that is trying to adapt to the modern professional sports economy but is continually stymied by the idiosyncratic relationship between the team, the stadium, and the owner.

Major League Baseball teams in 2020 have two basic tools at their disposal for maximizing revenue: their broadcast rights and their stadiums. Baseball has proven to have enormous value as a television property in the age of streaming television and PVRs because it can deliver nightly programming for six months of the year that the vast majority of viewers prefer to watch live, giving the networks that carry them the ability to promise advertisers that their commercials won’t be skipped. At the same time, the pace of the game offers unique opportunities for teams to generate value from the in-stadium experience. But the quirky ownership history of both team and stadium have created unique challenges for the Blue Jays on profiting from either revenue stream.

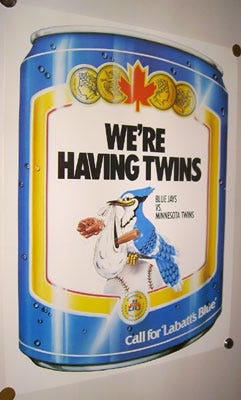

The Jays' first real push towards the postseason in 1985 consumed the city. Even as a 7 year-old, I could register that it was all anyone was talking about. It was a marketing bonanza for the team and its then-owners, Labatt Breweries. Labatt leveraged the opportunity to use their major league asset at every turn. Any schedule, flyer, poster, or banner that promoted the Jays also featured the stylized blue “Labatt” word mark rather prominently.

So atuned to the moment-by-moment co-branding opportunities was Labatt during that magical pennant race that the team and brewery distributed fresh posters to bars to rally fans for each 3-4 game series. One weekend when Boston was visiting it was “KNOCK THEIR SOX OFF”, replaced in short order by “WE’RE HAVING TWINS” before Minnesota came to town, then “KISS YOUR A’S GOODBYE”; each playful graphic rallying cry set inside a frame shaped like a can of Labatt Blue.

While Labatt was willing to put money into the Blue Jays in the team's early days to capitalize on the opportunity to market its own products, the move into the SkyDome in 1989 supercharged the team’s stand-alone revenue. The team became the first in MLB to reach 4 million in paid attendance in 1991. The money that gushed from season-ticket licences and corporate luxury boxes allowed the Jays to field a team featuring the highest payroll in baseball, leading directly to two World Series winners staffed by top-tier free agents. The two championships cemented the Blue Jays as a Canada-wide brand, which only multiplied the opportunities for its owners to sell more beer at a time when brands were tying themselves to national identity (Labatt’s principal competitor Moslon launched it’s iconic “I AM CANADIAN” branding exercise the year after the Jays’ second World Series victory).

That symbiotic relationship between brewery and team faltered when the Canadian owners of Labatt sold the brewery to Belgian giant InterBrew in 1995, and the baseball concern along with it. Suddenly the Blue Jays were in the hands of a foreign owner who had no understanding of the synergistic relationship between a Canadian beer and its symmetrically-named sports property. This confusion is somewhat surprising given that European soccer clubs had long been closely-held by corporations for decades prior to InterBrew’s foray into North America.

Nonetheless, the ambivalence of the conglomerate towards its sports property quickly became evident. As the 90s wore on and the new millennium approached the direction of the Blue Jays, both on the field and as a brand, became harder and harder to discern. Attendance and on-field performance, while not declining precipitously, stagnated in a murky middle. The team would make seemingly bold player acquisition moves, like signing once-dominant ace Roger Clemens, only to reverse course by trading him two years later. The marketing shifted from emphasizing the BLUE connection between team and beer to playing up its Canadian-ness, with a logo that more prominently accentuated the Maple Leaf. At the same time, it de-emphasized the us-against-them messaging that creates fierce attachment between brand and personal identity (“WE THE NORTH” anyone?) in favour of marketing that courted fans of other nearby teams, such as Yankee fans from Western New York, to take over the SkyDome when those teams visited.

Eventually the team returned to local ownership when it was bought by communications magnate Ted Rogers in 2000 and folded into the corporate structure of the telecommunications giant he had built. Rogers then acquired full control of SkyDome in 2004, which should have allowed the team to begin strategizing for ways to maximize the stadium’s revenue for the team. Instead, falling attendance due to anemic on-field performance led the team to tarp off several sections of the 500 level in the latter half of the 2000s.

The SkyDome had aged distressingly quickly. Launched amidst feverish boasts as a multi-use monolith to stand the test of time, even being dubbed “the eighth wonder of the world!”, seven fans were injured in 1995 as tiles fell from the facing of the 500 level during a game. The stadium was supposed to herald the next generation of multi-purpose municipal facilities that housed many teams and events to serve broader civic needs. Instead, North American sports teams immediately pivoted to bespoke stadiums that were meant to harken back to baseball’s rustic origins and become edifices the specific team, specific sport, the specific city could identify with. To compound this stylistic misstep, the Blue Jays lost a significant chunk of their corporate box revenue when the Air Canada Centre opened down the street in 1999. The new venue offered Toronto’s big spenders access to not only the Maple Leafs, the preferred outfit for Toronto’s Old Money, but the new Raptors just as Vince Carter was ascending to stardom.

The years between the SkyDome’s opening in 1989 and its acquisition by Rogers in 2004 saw a revolution in the relationship between MLB teams and their ballparks. The previous generation of stadiums were mostly the product of an era of rapid expansion of the sport, where ownership groups worked with city officials to construct or configure stadiums that met baseball's minimum requirements for a major league facility. The result was an era of baseball played in quaint, but slapdash and ill-fitting places like Park Jarry in Montreal, Candlestick Park in San Francisco, and Exhibition Stadium. The primary determinant of ticket price in these stadiums was proximity to the field, and concessions were mostly an afterthought.

When it was time for these facilities to be replaced, teams shifted their focus to creating a tailored ballpark experience that would more readily convince fans to part with their money. In addition to the corporate boxes that propelled revenue for the Blue Jays, teams added an increasing number of smaller tiers of pricing, particularly for seats closer to the field, topped off by luxury seats immediately behind home plate with concierge service. Concession stands became full restaurants that added a wide range of sought-after ballpark delicacies and craft brewery stands. To walk the concourse of a modern ballpark like Oracle Park in San Francisco, PNC Park in Pittsburgh, or the new Yankee Stadium is to be confronted with more opportunities to lighten your wallet than you’ll find anywhere outside a casino. The game itself is almost secondary to the Ballpark Experience.

But despite owning their ballpark for more than 15 years, the Blue Jays have not been able to similarly capitalize on the Rogers Centre. Shapiro has repeatedly publicly lamented that the team is among the bottom feeders of the league when it comes to generating revenue from its stadium. Where once the Blue Jays had towered above the league, other teams now run circles around them. The current configuration of the lower bowl features seats that are oriented towards centre field rather than home plate, and rows that are too gradually angled to have a clear view past the row in front of you without craning your neck. The resulting poor sightlines limit the potential for high-end tiers of seat pricing for the most valuable seats in the building.

The promised renovations to the dome were seen as a way to ameliorate some of these shortcomings. However, without knowing specifics, the fact that five years of hints at coming changes have not produced concrete plans or construction, particularly in a window of time when the facility is empty due to the covid-19 pandemic, suggests that number crunching has shown no renovations could improve the situation sufficiently to justify their cost. Increasing revenue from the stadium is particularly crucial for the Blue Jays because the team would maintain control of the income stream, compensating for the constraints on the other typically significantly income stream for MLB teams: broadcast revenue.

Ted Rogers perhaps bought the Blue Jays out of a sense of civic pride, but the purchase had the ancillary benefit of securing programming for Sportsnet, the sports speciality channel Rogers was about to acquire control of from CTV. This plan fit the evolving relationship between sports networks and teams described earlier, but with a significant and challenging twist for the Blue Jays: Most other teams either signed a broadcasting rights deal with a media company that was launching its own regional sports network, or launched a network on their own or with a broadcast partner, maintaining full or partial control over the revenues it generated. These revenues then accrue to the team, and in many large markets can run into the hundreds of millions annually, covering the lion’s share of a team’s on-field payroll before a ticket is sold.

But in the case of the Blue Jays, the network owns the team. So rather than broadcasting rights revenue appearing as a line item on the team’s balance sheet, the Blue Jays revenue (and more critically, its expenses) appear as a line item on Rogers’ balance sheet, mixed in with things like cable fees and iPhone sales. If the team itself receives any revenue from the broadcasting of its games, no one has been able to figure out how much. It would only be a paper transaction in any case, as one division of Rogers would simply be transferring money to another. Given that Blue Jays games have a Canada-wide audience in a nation of 35 million people, it’s reasonable to assume that a setup more akin to what teams like the Red Sox, Dodgers, or the Seattle Mariners enjoy would conservatively generate north of $100 million every year for the team. Instead that number rests at zero in every report one can find on the subject.

This isn’t to say that Rogers doesn’t invest in the team. Indeed, former General Manager Alex Anthopolous has in the past spoken highly of the Blue Jays’ corporate ownership structure, noting that he would get a clear budget number from Rogers at the outset of every season and then be given free reign with respect to how to use it. But this model can also have significant drawbacks for the on-field product. In 2015, when the Blue Jays were in their first legitimate playoff push since the World Series years, Anthopolous had to dip into the team’s available payroll to sign top-tier international prospect Vladimir Guerrero, Jr. for $3.9Million (USD). That limited the money available to acquire players at the trade deadline for the pennant race. Asking their corporate owners for an infusion of cash was a non-starter, particularly after a previous request before the 2013 season had not resulted in promised on-field contention.

In any case, the end result is that specific details of money flowing from ownership to the team are hard to pin down, and the Blue Jays are left without the ability to maximize team revenue from the two sources, broadcast rights and stadium, that provide most other teams in the league with their lion’s share of income.

Would rebuilding the stadium on the same site address this ongoing challenge? Hard to say since a rebuild would take five-eight years, leaving the team without any home at all for a significant stretch. And as noted, the ownership of the stadium offers still further complexities in that the team does not own the land on which it sits. The Globe’s recent reporting on the question insists the rebuild would be entirely privately funded. However, given that the land is owned by the Government of Canada, some type of transaction with the public sector would be required. Is Rogers prepared to pay full market price for one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in Canada before it spends a dollar on construction the Blue Jays’ new home? Would it do so only for the benefit of its baseball division?

If that option does not bear fruit, the reporting suggests Rogers would seek out an alternate site, perhaps on a site on the eastern waterfront land that was formerly to be occupied by Sidewalk Labs. Such a move would rob the Blue Jays of a home with unmatched transit access, to say nothing of undercutting one of the most lauded accomplishments of the SkyDome in the minds of those who ever attended an April game at Exhibition Stadium: getting the team away from the lake. Any other alternative sites would be similarly unable to match the current stadium’s transit accessibility. No wonder then that the search for a solution to the stadium equation has bedevilled the people who run the team for at least the last decade.

And so it goes. The Blue Jays play in what should be one of the sport’s most lucrative markets, at both a local and national scale. But they remain unable to tap into that potential because of a relationship with its television broadcaster where all the dials point in the wrong direction, and a stadium out of step with the times that they can’t seem to fix or replace.